Surrounded by water, built over the centuries with stone and wood, Venice looks like a city standing still in time. However, there was no shortage of opportunities to introduce significant novelties into the Venetian context, even exploring architectural languages that were distant from the ethereal aesthetics of the historic city.

A substantial part of these renewal proposals involved the creation of connections between the Venetian banks: projects, the latter, in many cases destined to remain on paper.

Alfred Neville’s Project for the Accademia Bridge. Published on Corriere del Veneto, 29/09/2017 (via web)

One of these untold stories soars between Campo della Carità and the Sestiere San Marco: it’s the Accademia Bridge, a structure with an eventful history, many times the subject of rethinking. Although the construction of a second bridge across the Grand Canal had been the subject of debate since the late 16th century, the connection between the two banks became an actual project only from 1852.

Encouraged by engineer Giuseppe Salvadori, endless debates took place regarding the type of bridge to be built: an opening bridge was thought of, and even an underground tunnel to preserve navigation, but the assumption was that the project would be carried out with the utmost respect for the city's decorum. Within two years, therefore, an iron bridge was erected by engineer Alfred Neville, a single span elevated about 5 meters above the water.

Drawing of Alfred Nevilles's Accademia Bridge, from: No replacement of Venice's Accademia Bridge, article published on dstandish.com, 1/12/2011 (via web).

The austere northern European style, so far from the city's traditional patterns, was never well liked by Venetians: for sixty years the serious impediment represented by the building's low height, which from time to time obstructed the transit of steamboats, was also ignored.

Load tests of the new Miozzi Bridge and the Neville Bridge being dismantled

Source: IUAV (via web)

When maintenance expenses began to become substantial, a competition was held to give the Accademia Bridge a new profile. Since 1932 several architects presented innovative solutions, but the winning design of the competition – a stone arch bridge designed by architect Duilio Torres and engineer Ottorino Bisazza – never came to life. Just a month before the results of the competition came out, Eugenio Miozzi erected a temporary version of the Accademia Bridge, a larch wood structure intended to last until the construction of the new design, which due to the war was never completed.

Carlo Scarpa also participated in the competition, with a significantly modern design: a horizontal walkway was supported by two large concrete heads placed on the banks, by means of two connecting stairways. Scarpa also made tempera sketches directly on some photos of the context as if to verify the impact of the architectural structure on its surroundings, but like the rest of the modern-inspired projects, it was set aside. As if to underscore this deep-rooted attachment to tradition, restorations of the Miozzi Bridge became more and more frequent from the 1950s, earmarking a temporary project to become permanent.

Carlo Scarpa, Competition projects for the Accademia Bridge

Source: Venezia di carta, curated by Alessandra Ferrighi, LetteraVentidue, 2018.

However, there was no lack of opportunities to give voice to important innovations: there were projects, but they remained on paper; there were impulses motivated by the desire for novelty, but always seeking a juxtaposition with traditional values.

On more than a few occasions Venice (as well as Italian centers, when compared to the major European cities) has shown itself intolerant or indifferent to contemporaneity: suffice it to mention the many criticisms aroused by Santiago Calatrava's intervention for the Constitution Bridge, an innovation considered out of context, but a project that nevertheless succeeded in landing where others had failed. The architect played with sinuous forms and alternating traditional materials (steel and Istrian stone) with more unusual ones (glass): some of the first criticisms precisely concerned the use of this material, unusual for this type of infrastructure.

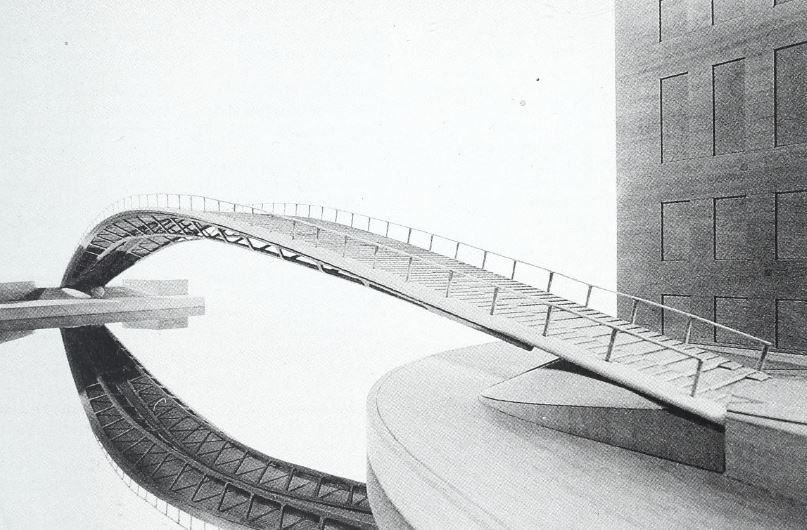

Constitution Bridge. Source: Philip Jodidio, Calatrava. Complete Works 1979-today, Taschen;

Scale model of the Constitution Bridge; Source: Luca Molinari, Santiago Calatrava, Milano, Skira, 1998;

Constitution Bridge, Venice; Source: Ian Bramham photography (via web).

Luciano Vistosi's lesser-known project, which proposed an all-glass reinterpretation of the Accademia Bridge in 1983, also remained unimplemented: a glass deck was sustained by a steel supporting structure. The idea came to the designer on a winter afternoon while observing the Devil's Bridge (in the island of Torcello), which was covered by a thick sheet of ice: hence the decision to reproduce a glass bridge that would cross the Canal "like a blade of light."

Vistosi was aware of the risks involved in presenting such an innovative project, but he pursued the proposal with the idea of making the city of Venice more liveable through structural research.

Yet, the history of Venice also outlines through missed opportunities and forgotten projects: they represent a stance that places the city on the fine line between the desire for renewal and the tendency to stand alongside what is known, what is tradition.

Projects for the Accademia glass Bridge, Luciano Vistosi

Source: Luciano Vistosi, Oltre il vetro. Glass and Beyond, Grafiche Veneziane, 2003